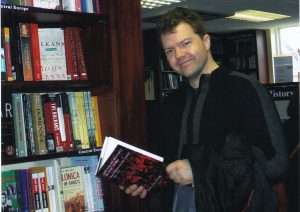

Dr. Marko Attila Hoare is an Associate Professor of Economics, Politics and History at Kingston University in London, UK. The author of four books on Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH), his most recent text, The Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War, is now available from Oxford University Press. His first book, How Bosnia Armed, is arguably the most significant study of the military-political aspects of the Bosnian War and has regained critical currency today because of events in Ukraine—ones bearing striking (and deeply troubling) similarities with the Bosnian experience.

Dr. Marko Attila Hoare is an Associate Professor of Economics, Politics and History at Kingston University in London, UK. The author of four books on Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH), his most recent text, The Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War, is now available from Oxford University Press. His first book, How Bosnia Armed, is arguably the most significant study of the military-political aspects of the Bosnian War and has regained critical currency today because of events in Ukraine—ones bearing striking (and deeply troubling) similarities with the Bosnian experience.

A leading commentator on Balkan and global affairs more generally, Dr. Hoare has developed a reputation as a preeminent scholar and historian of the region. In the run up to a month-long series of commemoration around Europe and BiH of the anniversary of the beginning of the First World War, I spoke with Dr. Hoare about the on-going contest of histories and narratives in the former Yugoslavia and the continued, slow-moving catastrophe of contemporary EU and US policy towards BiH.

Various commemorations of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and the beginning of World War I will be marked throughout the month of June in BiH. The origins of the war, the role of Gavrilo Princip and his connections with the Serbian secret service at the time have, as a result, become a hot topic. But most of the accounts and debates we are seeing play out in the local media have very little basis in actual historical research or analysis. What is their function then, do you think?

The legacy of the Sarajevo assassination is still a politically controversial topic, and history continues to divide people in the former Yugoslavia. Many Bosniaks and Croats, in particular, view the assassination as a terrorist act whose consequences – the outbreak of World War I, collapse of Austria-Hungary and establishment of the Yugoslav kingdom – amounted to a disastrous, historic wrong turn for the peoples of Bosnia-Hercegovina. Whereas for many others – including many Serbs, those who still identify with Yugoslavia and many outside observers – Princip and his fellow assassins are viewed more sympathetically, as reacting against an unjust imperialist occupier. This division of opinion relates to whether the goal of Bosnia-Hercegovina’s unification with or annexation to Serbia, and Serbia’s military effort during World War I, are viewed positively in terms of national liberation and unification or negatively in terms of Serbian expansionism. Much commentary on the assassination and outbreak of war is likely to be motivated by the desire to uphold one or other of these competing narratives.

As a historian then, is there anything about this particular moment that can help us think about BiH in the one hundred years since then? Is there anything other than a purely symbolic connection between 1914 and 2014?

At one level, the assassination formed one act in the long history of Serbian attempts to expand westward into Bosnia-Hercegovina, and of the desire of some Bosnians to unite with Serbia. And it was a decisive act, because the chain of events it set in motion resulted in the establishment of the Yugoslav state, which changed the rules of the game. The establishment of Yugoslavia ended neither the struggle for Bosnian self-rule nor the struggle of Serb and Croat nationalists to annex Bosnia-Hercegovina to Serbia and Croatia respectively, but it did mean that these struggles were fought on a different basis. And they became more bitter. The catastrophes that befell Bosnia-Hercegovina’s peoples since then, culminating in the Ustasha and Chetnik genocides of World War II and subsequently the Bosnian genocide of the 1990s, can be traced back to the flawed form of Yugoslav unification of 1918-21, which in turn arose out of World War I. The Bosnian question, and the Serb and Croat questions within Bosnia-Hercegovina, are very much alive today, and we do not know how they will be resolved. But we cannot understand the form these questions take today unless we understand their historical background, and that includes what happened in 1914.

A few months ago you gave an interview to the Dnevni Avaz newspaper in which you argued that the “experiences of 1992-95 should have taught Bosnians that they can never count on the West” and that “the EU and US have lost the will to push for the reintegration of Bosnia and are once again appeasing the separatism of the RS leadership.” Since then we’ve witnessed significant protests in BiH, the emergence of civic assemblies and something of a panicked response on the part of the international community to account for this popular anger. Do you now see any signs of a potential change in policy on the part of the EU or the current US administration when it comes to BiH?

Unfortunately not. The EU and US will be content above all if Bosnia-Hercegovina remains quiet and does not become once again a source of regional and European instability. The present phase in Western politics is one of exceptional small-mindedness. Expansion fatigue or outright opposition to expansion is strong in the EU; Euroscepticism, Islamophobia and hostility to immigration are driving the far-right forward; and the Obama administration in the US is pursuing an exceptionally timid conservative-realist foreign policy involving a retreat from global leadership and responsibility. In these circumstances, Western policy toward Bosnia-Hercegovina is unlikely to change unless a compelling reason arises for self-interested, risk-averse Western statesmen to change it. Short of a new crisis erupting in the region that seriously jeopardises European stability and Western security, it is difficult to imagine that happening. The protests in Bosnia-Hercegovina have not assumed a scale significant enough to qualify. Protests brought about significant change in Ukraine, but only after the president had been driven from office.

Speaking of policy, what is actually at stake in BiH for the EU and the US? The lack of sustained engagement on the part of Brussels and Washington would seem to suggest that they believe BiH’s geopolitical significance to be marginal. Is this so?

Yes. Bosnia-Hercegovina is not strategically important for the EU and US, which explains the failure of intervention in 1992-1995 and the failure to re-establish a functioning Bosnia-Hercegovina since then. Bosnia-Hercegovina is less strategically important than Kosovo and Macedonia, where a serious conflict could potentially drag in NATO states Greece and Turkey on opposite sides. The West perceives its principal interest in Bosnia-Hercegovina in terms of keeping the country quiet so that it does not become a source of regional and European instability. Bill Clinton’s US ultimately intervened to force the Bosnian Serb rebels to accept a peace agreement in the summer and autumn of 1995, because the conflict was seriously damaging its relations with its European allies and the President’s political standing at home. If Bosnians want the outside world to take an interest in them again, they need to rock the boat.

Since we’re on the subject of flashpoint regions, in your first book, How Bosnia Armed, you describe in striking detail how difficult it was for the Sarajevo government to organize the defence of the then Republic of BiH in the early days of the war, as much for the lack of arms as for a slew of high profile defections. To a certain extent, one cannot help but see the parallels with the situation in Ukraine. Is there anything Kiev can learn from BiH’s experience in the 90s?

Yes. The Bosnian experience should teach Ukraine that it can only rely on its own national strength and effort to defend its independence and territorial integrity; that it should on no account rely on or trust the West to defend it or its interests; and that it should avoid any negotiations over constitutional change or regional autonomy that might encourage Russia and its separatist rebels to fragment the country further – as the Lisbon Agreement and Vance-Owen Plan encouraged Milosevic and Karadzic. The Bosnian experience should teach Ukraine that the West is likely to reward the unreasonable and punish the weak, so Kiev should never, under any circumstances, restrain its own military and political effort at self-defence for the sake of appearing reasonable. Biti bezobrazan [being insolent or brazen] – that’s the way to defend one’s country.

Interview by Jasmin Mujanović | @JasminMuj

http://edi-dc.org/hoareinteview/