Who are Bosniaks?

Bosniaks are an ethnic group in the Southeastern part of Europe, mainly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also present in the neighboring region of Sandzak (Serbia and Montenegro) and countries that were part of former Yugoslavia (North Macedonia, Kosovo, Croatia, and Slovenia). Bosniaks got their name after the river Bosna that flows from its source at the foothills of the Mount Igman, on Sarajevo’s outskirts, northward and through Bosnia’s heart.

Bosniak History – Middle Ages

The earliest known inhabitants of the area were the Illyrians (during Roman Empire). In the 7th century, Slavs settled in the region and brought new customs and culture, with the local population soon adopting the Slav language.

Unlike other countries in Europe or the Balkans that are mostly nation-states, from its beginning over 800 years ago, Bosnia was a region where western and eastern cultures and ways of life met and often integrated, but also sometimes clashed. From the 10th century, the border between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christian areas ran right through Bosnia. Back then, people of Bosnia attended three different churches: 1) Roman Catholic, 2) Orthodox Christian, and later on 3) Bosnian church, which was considered heretical by the other two.

By the end of the 14th Century, the Kingdom of Bosnia was the most powerful state in southeast Europe. At the peak of its power and dominance in southeast Europe, the Kingdom of Bosnia included most of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, a large piece of the Dalmatian coast (Croatia), and a significant land in Serbia and Montenegro (Sandzak region and coastal area).

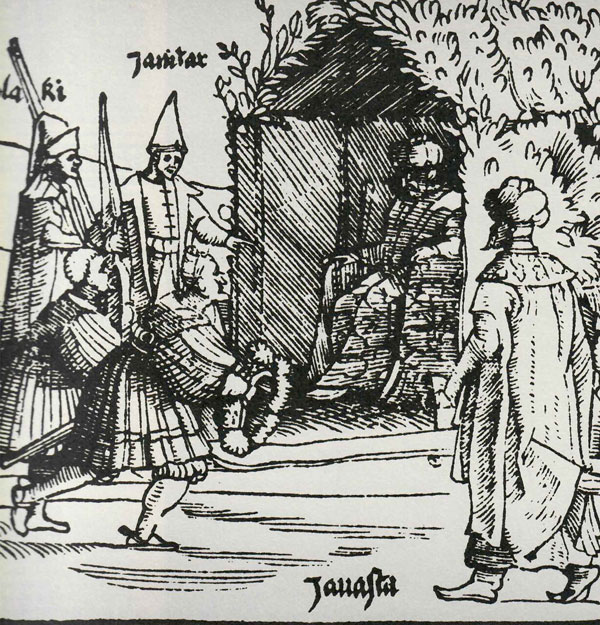

The conquest of the country by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century saw Islamic and Jewish faiths. Still, Bosnia remained recognized as a separate region within the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman authorities referred to the people of the Province of Bosnia (which included present-day Bosnia – Herzegovina and Sandzak region in present day Serbia and Montenegro) as Bosniaks, irrespective of their faith.

Bosniak History – Berlin Congress

In the 19th Century, following the Berlin Congress, the Province of Bosnia was split between Austro Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. The present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina remained under the Austro Hungarian protection (later annexed), while Eastern Bosnia (today’s Sandzak region) remained under the Ottoman rule for a short period. Following Serbia and Montenegro’s Independence, however, Sandzak was split between these two newly established countries.

During their short rule, Austro Hungarian Empire introduced many technological and scientific advances, and Bosnia and Herzegovina started to develop quickly. At the same time, the new Empire changed the local alphabet from Arabic to Latin, making most of the population illiterate overnight (locals used the Arabic alphabet for the prior 450 years). It would take more than a generation for the local people to increase the literacy rate.

It was during the Austro-Hungarian rule that Bosnia’s name changed to Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina are two geographical regions with different landscapes and climates). Finally, during this time, Austro Hungarians attempted to change the nationality of local people, promoting the concept of a Bosnian nation. This effort succeeded only with a smaller segment of the population (mostly Muslims). Simultaneously, the Bosnian Orthodox population adopted the label Serbs, while the Bosnian Catholics started identifying as Croats, aligning themselves with people in neighboring Serbia and Croatia.

Bosniak History: Yugoslavia

With the establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (originally called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), Bosniaks were no longer recognized as a distinct ethnic group; instead, they were to identify as either Serbs or Croats. Following World War II and the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the same policy of depriving Bosniaks of their rights, including the right to their name, persisted.

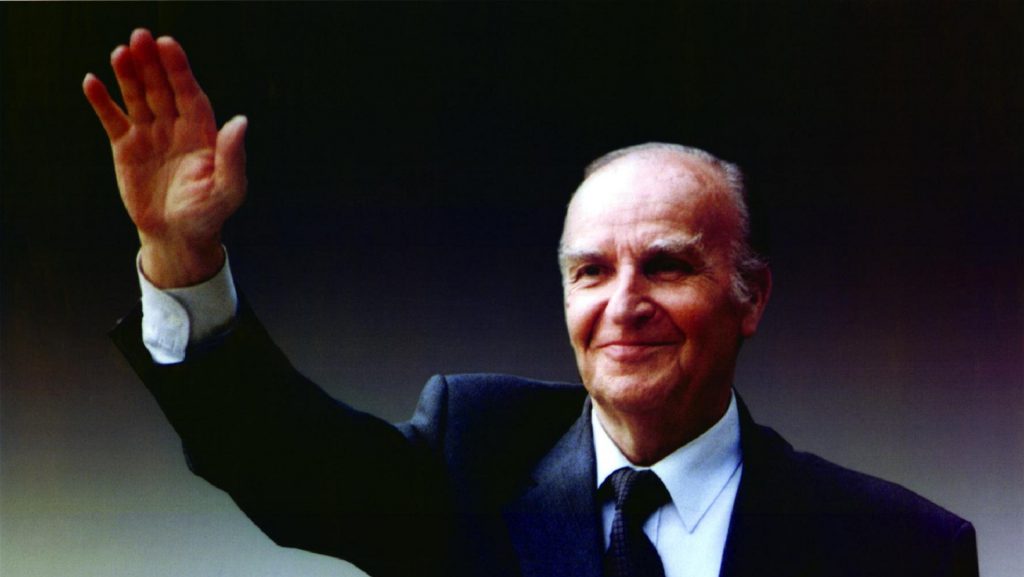

In the 1960s and 1970s, Yugoslavia became a leader and a significant player in the Non-Aligned Movement (a forum of 120 developing states). Most of the countries of the Non-Aligned Movement had significant local Muslim populations. The Non-Aligned Movement countries were essential to communist authorities as they presented a significant economic opportunity and opened the door to large markets for many Yugoslav companies. The Communist leaders amended the Yugoslav Constitution, declaring Bosniaks as constituent people in the Yugoslav Federation. Bosniaks were not recognized under their historic name, however, but instead under the “Muslim” identity. The specific religious designation of identity fit the Communist agenda with other countries of the Non-Aligned Movement. Therefore, it was “Muslims,” rather than Bosniaks, that became a recognized ethnic group in Yugoslavia. To further prove the point and raise international awareness of Muslims living in Yugoslavia, in 1971 the new Prime Minister of Yugoslavia became “Muslim” Dzemal (Jamal) Bijedic. Bijedic would die in a mysterious plane accident six years later.

Bosniak History – Bosniaks reclaimed their historic name in 1993

Following Yugoslavia’s break up, Bosnia and Herzegovina held an independence referendum resulting in two thirds of the population favoring the independence. As a result, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on March 1st, 1992 and its first President became Alija Izetbegovic. On September 28th, 1993, under the most challenging circumstances and while Sarajevo was under military siege and heavy shelling by the Bosnian Serb Army, Bosniak leaders issued a Declaration, reclaiming their historical name.

Today, most Bosniaks identify themselves with Bosnia and Herzegovina as their ethnic state and are part of such a common nation. Around two million Bosniaks live in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Regionally, the largest number of Bosniaks outside of Bosnia and Herzegovina live in Montenegro and Serbia (with the largest concentration of Bosniaks living in the city of Novi Pazar). A smaller autochthonous population of Bosniaks is present in Croatia, Kosovo, Slovenia, and Macedonia.

Bosniak Culture

Although Bosniaks represent a small ethnic group globally (~5 million), they have an incredibly rich and diverse cultural heritage. Several cultural and historical narratives originate in the Bosniak tradition, heritage, and experience. The sociological phenomenon of drinking coffee, cultural phenomena such as Stecci tombstones, Sevdah as an integral part of Bosniak music culture, stories of centuries of peaceful co-existence such as the famous Sarajevo Haggadah, and the story of Gazi Husrev Bey and Sahdidar Hanume, to name a few, remind us that one lifetime is long enough to make a lasting impression on a community and humanity.

Bosniaks are often noted for their unique culture, which is influenced by eastern and western civilizations and schools of thought over their history. The Bosniak nation is controlled by oriental and western culture due to its Ottoman roots and geographical advantage.

Bosniaks take pride in the melancholic folk songs “sevdalinke,” the precious medieval filigree manufactured by old Sarajevo craftsmen, and a wide array of traditional wisdom carried down to newer generations by word of mouth and written down in numerous books.

Historical figures remain national heroes, their life and skill in battle emphasized through storytelling and writings. Old Slavic influences can also be seen, such as Kulin Ban, who has acquired legendary status. Ban developed the economy and practiced a policy of religious freedom almost unique for his time.

Bosniak History – Bosniak Genocide and Forced Migration

Throughout history and most notably in the 20th century, Bosniaks endured periods of ethnic cleansing and genocide. These conflicts had a tremendous effect on the respective population’s territorial distribution. The destruction of towns and villages, expulsion of inhabitants, systematic looting, and raping of women, left deep scars and an abiding hatred between communities that once lived together and even intermarried.

When Europeans started to remove their iron curtains, and as the Berlin wall crumbled in the late 1980s, the ethnic groups in former Yugoslavia began building their walls and curtains. Unhappy with the constitutional changes that would significantly strengthen the powers of the capital of Yugoslavia Belgrade, which also happened to be the capital of the Republic of Serbia, first Slovenia, and then Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia. It was not until Macedonia declared its intention to leave the South Slav union that Bosnia and Herzegovina followed suit and organized a referendum on independence in March of 1992.

However, a political party in Bosnia called the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), headed by the now-indicted war criminal Radovan Karadzic, publicly called on the Bosnian Serbs to boycott the referendum. Nonetheless, two thirds of the population voted in favor of Independence, including a significant number of Bosnian Serbs. Unhappy with the referendum results, the Serbian Democratic Party intentionally withdrew from the numerous institutions of the newly independent country and declared their republic, called Republic of Srpska or the Serb Republic, within the sovereign territory of BiH. Their President became Radovan Karadzic, and they formed a Bosnian Serb army whose general would become Ratko Mladic.

While the world recognized the newly independent Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Security Council of the UN placed an arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina. After the Yugoslav People’s Army handed over their weapons to the Bosnian Serb Army, the world was soon in shock over prisoners’ pictures in concentration camps, the shelling of towns and civilians, and “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia became a common household term. According to the International Red Cross Committee data, “200,000 people were killed during the Bosnian war, 12,000 of them children, while 50,000 women were raped, with 2.2 million people forced to leave their homes.”

The culmination of these atrocities was the Srebrenica genocide. This event was marked by the genocide of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in Srebrenica, at the time an enclave and a UN “safe haven,” that promised to protect but miserably failed to do, finally prompting NATO intervention. And as soon as NATO intervened against the Bosnian Serb Army, the war was over. With the U.S. as a mediator, the parties came together in Dayton, Ohio, to negotiate a peace accord in November of 1995, officially ending the war. Today many of the Bosniaks are war refugees, or direct descendants of Bosniak refugees, resettled in Western countries.

Bosniaks in North America

Bosniaks sought refuge throughout the United States and Canada. The first Bosniaks settled in Chicago in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, joining other immigrants seeking better opportunities and better lives. In 1906, Bosniaks established its first organization called Dzemijjetu-l-hajrijjeh. Chicago’s Bosniak community received a new influx of migrants after World War II. The War in Europe and the communist takeover forced many to seek new lives outside of the European continent. This new wave of refugees included many well-educated professionals. These individuals sought a safer and better experience for their families and were therefore willing to take on lower-skilled jobs as factory workers, kitchen aids, and janitors.

During and after the 1992 – 1995 Bosnian war, another massive wave of Bosniaks sought refuge in the United States. The people of Bosnia and Herzegovina sought stability and new beginnings in North America.

Bosniak Communities in the United States

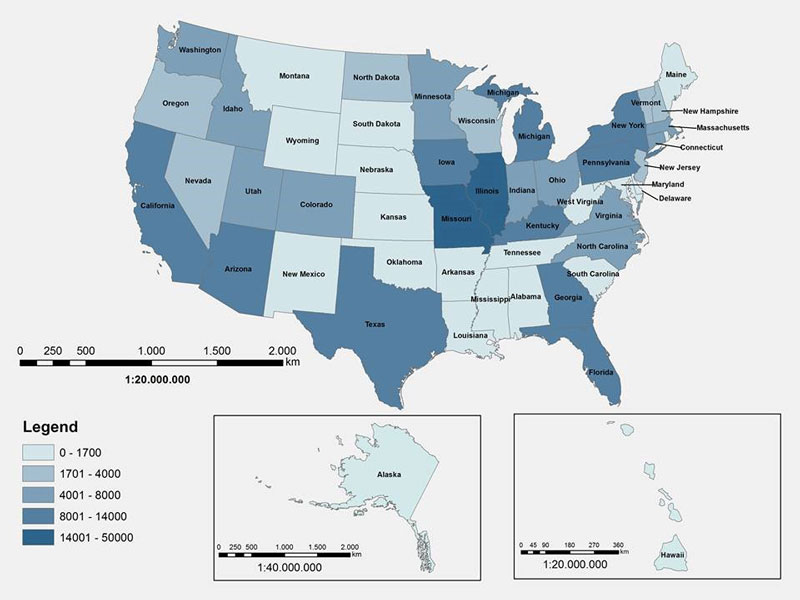

Metropolitan St. Louis quickly became the epicenter for Bosniaks migrating to the United States. According to the U.S. Census, more than 40,000 refugees moved to the St. Louis area in the 1990s. By 2016, that number had risen to some 60,000 Bosniaks living in St. Louis.

While St. Louis and Chicago are notable for the large number of Bosniaks, they not the only areas that Bosniaks have come to call home.

Looking through immigration settlements throughout North America, one can find many similar stories of Bosniak resettlement in a number of U.S. cities, including Atlanta (GA), Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Erie (PA), Jacksonville (FL), Des Moines and Waterloo (IA), Phoenix (AZ), Seattle (WA), Louisville and Bowling Green (KY), Detroit (MI), Utica and Brooklyn (NY), Boston (MA); Twin Falls (ID), Cleveland (OH); Nashville (TN), Greensboro (NC), Oklahoma City (OK), Houston (TX),), greater San Francisco, LA and San Diego (CA); and Portland (OR). Today, it is estimated that over 300,000 Americans of full or partial Bosniak descent live in the United States.

Bosniak Communities in Canada

In Canada, as in the United States, Bosniaks sought refuge and a better life for themselves and their families. Similar to the communities in the United States, Bosniaks have large communities throughout Canada. While the majority of Bosniaks immigrated to Canada as a result of the 1992-1995 war, historically, Bosniak migration to Canada dates back to the 19th century.

Bosniaks have a notable presence throughout Canada, many of whom reside in Greater Toronto (Etobicoke and York districts, Mississauga, Brampton and Rexdale), Hamilton, London and Windsor (ON), Montreal and Quebec City (QC), Edmonton and Calgary (AB), Vancouver and Victoria (BC), Winnipeg (MB) and other cities. Today, it is estimated that over 50,000 Canadians of full or partial Bosniak descent live in the country.